Why Scrum Fails often

In my years of working with Scrum teams across various organizations, I’ve witnessed a recurring pattern: Scrum implementations fail. Not because Scrum doesn’t work – but because most environments aren’t ready for what Scrum actually demands.

Let’s break it down.

WHAT IS SCRUM, REALLY?

Scrum is not a magic trick to make things faster, cheaper, and better overnight. It’s a framework designed to tackle complex problems by developing adaptive solutions.

Understanding Scrum goes beyond knowing events, roles, and artifacts. At its core, Scrum is built on essential foundations:

EMPIRICAL PROCESS CONTROL

Scrum operates in environments where not everything can be predicted. That’s why it’s based on empiricism — making decisions through observation, experience, and continuous learning.

The three pillars of empiricism are:

- Transparency - Make process, work, goals, and progress visible to everyone.

- Inspection - Regularly check outcomes, processes, and progress.

- Adaptation - Adjust as soon as deviations or improvements are identified.

Example:

A team developing new product features cannot rely on a perfect upfront plan. Instead, through planning short Sprints, regular Reviews, and Retrospectives, they inspect & adapt — discovering what truly delivers value, and changing direction when needed.

THE SCRUM VALUES – MORE THAN JUST WORDS

According to the Scrum Guide, successful use of Scrum depends on how well people embody its five core values:

Commitment

“The Scrum Team commits to achieving its goals and to supporting each other.”

It’s about dedication — to the Product/Sprint Goal, to quality, and to the team. Facing unexpected challenges, a strong team doesn’t abandon their goal. They commit to overcoming obstacles together, even if it means stepping out of comfort zones.

Focus

“Their primary focus is on the work of the Sprint to make the best possible progress toward these goals.”

Scrum demands that teams protect their focus from distractions. When ad-hoc requests pop up, a focused team defends their Sprint boundaries, ensuring they stay aligned with delivering what truly matters.

Openness

“The Scrum Team and its stakeholders are open about the work and the challenges.”

Being open fosters trust and early problem-solving. Instead of hiding delays, a team openly shares blockers during Daily Scrums, enabling quick support and avoiding last-minute surprises.

Respect

“Scrum Team members respect each other to be capable, independent people, and are respected as such by the people with whom they work.”

Respect empowers teams to self-organize and thrive. A Product Owner trusts the Developers to decide how to deliver the best solution, while Developers respect backlog priorities set by the PO.

Courage

“The Scrum Team members have the courage to do the right thing, to work on tough problems.”

Courage is key to challenging assumptions and addressing uncomfortable truths. A team notices that continuing with a planned feature won’t add value. They have the courage to speak up, pivot, and suggest a better alternative — even if it disrupts expectations.

Why These Foundations Matter?

Many teams “do Scrum” — but without living these values or embracing empiricism, they miss the point.

- They hold daily standups but avoid real transparency.

- They run retrospectives but never truly adapt. Action items get lost in the rumble.

- They recite the values but don’t embody them when it gets tough.

Reminder: Agile is a mindset. Scrum is a framework.

Scrum can be agile – but just using Scrum doesn’t make you agile.

Ask yourself:

Does your team truly embrace transparency, inspection, adaptation — and live the Scrum values?

Or are you just going through the motions?

SCRUM: AGILE ISLAND IN A TRADITIONAL OCEAN

It’s understandable that organizations, eager to become more adaptive, turn to Scrum as a solution.

However, when introduced into environments shaped by traditional structures and mindsets, Scrum often finds itself isolated — like an agile island surrounded by conventional waters.

In many cases, leadership invests in Scrum trainings and expects quick wins. The Scrum Team begins to “do agile”, while the broader organization continues to operate with familiar patterns:

- Fixed scope, budget, and timeline as measures of success

- Hierarchical decision-making, where approvals slow down innovation

- A focus on following plans rather than delivering value

Within this context, teams are encouraged to self-organize — but only within predefined boundaries.

Freedom is offered, yet tied to delivering exactly what was outlined months ago.

Self-organization is welcomed, as long as every decision is reported and approved.

These dynamics aren’t driven by bad intentions. They often stem from a deep-rooted desire for control, predictability, and risk avoidance — values that served well in simpler, more linear environments.

A real-world example illustrates this tension:

In a large corporation I supported, a Scrum Team worked with a backlog entirely dictated by senior management. Sprint Goals were reduced to checklists. The Product Owner had little influence, and Daily Scrums were overseen by a Project Manager tracking status updates.

It’s easy to see how, in such a setting, frustration grows — leading to the conclusion:

“Scrum doesn’t work here.”

But perhaps the question isn’t whether Scrum works, but whether the environment allows agility to unfold.

Recognizing these systemic constraints is a good step towards understanding that Scrum isn’t designed to function as a process improvement within traditional frameworks — it’s meant to challenge them, fostering adaptability, collaboration, and value-driven thinking.

THE WRONG EXPECTATIONS: FASTER, BETTER, CHEAPER?

When organizations adopt Scrum, challenges often begin with misaligned expectations.

It’s understandable that, driven by the desire for improvement, many hope to gain the benefits of agility — faster delivery, clearer forecasts, and better efficiency — without significantly changing existing structures or mindsets.

These expectations are not uncommon, but they can lead to frustration when Scrum is seen as a tool for optimization rather than as a framework for adaptability and learning.

Let’s explore some typical misconceptions that frequently set Scrum initiatives on a difficult path.

THE WRONG EXPECTATIONS: FASTER, BETTER, CHEAPER?

When organizations adopt Scrum, challenges often begin with misaligned expectations.

It’s understandable that, driven by the desire for improvement, many hope to gain the benefits of agility — faster delivery, clearer forecasts, and better efficiency — without significantly changing existing structures or mindsets.

These expectations are not uncommon, but they can lead to frustration when Scrum is seen as a tool for optimization rather than as a framework for adaptability and learning.

Let’s explore some typical misconceptions that frequently set Scrum initiatives on a difficult path.

1. SCRUM AS A QUICK FIX — WITHOUT CHANGING THE ORGANIZATION

“We’ll implement Scrum, but everything else stays the same.”

It’s a common belief that Scrum is simply a modern process improvement — a faster way to deliver projects within existing frameworks.

In this view, results are expected without addressing:

- Hierarchical decision-making

- Micromanagement habits

- Fixed scopes and rigid plans

- Legacy processes

Yet Scrum invites more than operational tweaks — it encourages organizational change.

Expecting self-organization while maintaining command & control structures creates a natural tension.

Similarly, agility cannot thrive if leadership and culture remain anchored in waterfall thinking.

For example:

A company introduces Scrum, but middle management continues assigning tasks, requesting daily status updates, and insisting on detailed upfront planning.

The outcome? Frustrated teams, surface-level agility, and little real improvement.

Recognizing that Scrum challenges traditional structures is a good step towards aligning expectations with reality.

2. SCRUM AS A TOOL FOR CONTROL, PREDICTABILITY & EFFICIENCY

“Scrum will give us faster delivery, clear forecasts, and better resource utilization.”

Under pressure to deliver more with less, it’s understandable that organizations hope Scrum will restore predictability and increase efficiency.

This often leads to viewing Scrum as a method to:

- Deliver more in less time

- Regain control in complex environments

- Reduce costs while boosting output

However, Scrum isn’t designed as a control mechanism.

It’s a framework for embracing complexity, fostering fast feedback, and enabling continuous adaptation.

Yes, Scrum can accelerate value delivery — but only when teams focus on learning and responding to change, rather than adhering to rigid plans.

For instance:

Management asks, “When will everything be delivered? We need a final delivery date — can you provide it after Sprint 1?”

This reflects a desire for certainty but overlooks Scrum’s purpose: iterative discovery and flexibility.

Understanding this shift from control to adaptability is a good step towards using Scrum effectively.

3. SCRUM AS A ONE-SIZE-FITS-ALL SOLUTION

“Let’s use Scrum everywhere — for every type of work.”

In the enthusiasm to adopt agile practices, some organizations apply Scrum universally, regardless of context.

While Scrum excels in complex, evolving environments, it’s less effective for:

- Routine, predictable tasks

- Maintenance or operational workflows

- Teams dealing with low variability

Example:

I once worked with a support team required to operate in Sprints to process incoming tickets.

Sprint Goals felt artificial, Reviews became formalities, and much of the effort went into following the framework rather than delivering value.

Recognizing that different types of work call for different approaches — such as Kanban for flow-based tasks — is a good step towards applying agility where it fits best.

By reflecting on these expectations, organizations can begin to see Scrum not as a universal solution or a shortcut to efficiency, but as a framework that supports adaptability, learning, and value-driven delivery — when applied in the right context and with the right mindset.

WHY MOST ORGANIZATIONS AREN’T READY FOR REAL SCRUM

When organizations embark on their Scrum journey, they often carry with them long-standing habits and beliefs shaped by traditional ways of working.

It’s not unusual that these patterns influence how agility is interpreted and applied — often leading to friction between intention and execution.

Here are some typical areas where this disconnect becomes visible:

1. OUTPUT OVER OUTCOME

Measuring output offers comfort. It provides clear numbers, visible progress, and aligns with familiar performance metrics. That’s why many organizations continue to equate success with the volume of work delivered — a legacy of traditional development thinking.

Scrum, however, encourages a shift in focus: from delivering more to delivering what truly matters.

Reframing success around outcomes rather than output can be a meaningful step towards value-driven delivery.

2. PROJECT THINKING INSTEAD OF PRODUCT THINKING

The reliance on fixed requirements often reflects a desire for certainty.

Yet in complex environments, predefined solutions rarely survive first contact with reality.

Scrum supports teams in navigating uncertainty by fostering continuous discovery and alignment with evolving user needs.

Moving from a mindset of “delivering what’s specified” to “solving the right problems” helps unlock the true strength of agile product development.

3. SELF-ORGANIZATION? NOT QUITE

The concept of self-organization can feel unfamiliar — especially in environments where control and task management have long been the norm. It’s common for middle management to continue directing work, unintentionally limiting team autonomy.

When teams lack empowerment, they may follow Scrum practices mechanically, without embracing ownership.

Creating space for self-organization requires more than permission — it calls for a cultural shift towards trust and enabling teams to make decisions.

4. CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT AS AN AFTERTHOUGHT

While inspect & adapt is central to Scrum, improvement efforts are often overshadowed by delivery pressures. Retrospectives get postponed, difficult topics remain unspoken, and reflection is seen as optional.

This tendency to prioritize short-term outputs over long-term growth is understandable in fast-paced environments — but it comes at the cost of resilience and adaptability.

Embracing continuous improvement as an integral part of work, rather than a luxury, strengthens a team’s ability to navigate complexity.

5. THE MISSING INGREDIENTS: TRUST, COURAGE, PATIENCE & DISCIPLINE

Scrum invites behaviors that challenge conventional corporate logic:

- Trusting people to self-organize around value

- Addressing uncomfortable realities

- Waiting for systems and teams to mature

- Consistently applying simple rules

These qualities don’t emerge overnight — and many organizations struggle to nurture them.

Acknowledging that these traits are foundational, not optional, can pave the way for sustainable agility.

By becoming aware of these recurring patterns, organizations can better understand why Scrum often feels difficult to realize in practice.

It’s not the framework that creates resistance — it’s the confrontation with established mindsets and structures.

This awareness marks an important step towards creating conditions where Scrum can deliver more than just ceremonies — but real value, adaptability, and growth.

THE CEREMONY TRAP

Scrum invites people to engage in a dynamic, value-driven process — one that can feel uncertain and challenging at times. In response to this uncertainty, teams and organizations often find stability in the visible structures of Scrum: Sprint Planning, Daily Scrum, Sprint Review, and Sprint Retrospective.

It’s understandable that, in a complex environment, these ceremonies can become something to hold onto — offering a sense of routine and control. They all offer opportunities for inspect & adapt, but when the focus shifts to simply performing these events, their original purpose may fade into the background.

In many cases, teams experience these meetings more as obligations than opportunities.

Retrospectives might be postponed when immediate tasks seem more pressing, or they turn into mere discussions about problems with solutions, while opportunities for improvement remain unused.

Plannings can be influenced by external expectations, turning collaborative forecasting into commitment setting.

Reviews sometimes become presentations rather than valuable feedback loops.

And the Daily Scrum may slip into status reporting instead of fostering team alignment and adaptation.

We have probably all seen these anti-patterns in action too often. When this happens, the ceremonies risk becoming routine activities, disconnected from the value they were designed to create.

Factors such as fear of uncertainty, a desire for control, lack of psychological safety, an unclear understanding of agile principles — and the courage to apply these principles — can all contribute to this dynamic, gently guiding teams into what can be called the ceremony trap.

Recognizing this pattern is a good step towards reconnecting with the true intent behind these events: fostering communication and collaboration, creating transparency, and continuously improve the why, how and what.

CONCLUSION: SCRUM DOESN’T FAIL – WE DO

When Scrum initiatives struggle, it’s rarely because of the framework itself.

More often, challenges arise from how Scrum is approached — shaped by existing mindsets, structures, and expectations.

Perhaps the more powerful question isn’t, “Why isn’t Scrum working for us?” but rather,

“Are we truly ready to work the Scrum way?”

Embracing this reflection is a good step towards unlocking Scrum’s true potential — not as a shortcut to faster results, but as a catalyst for meaningful, sustainable change.

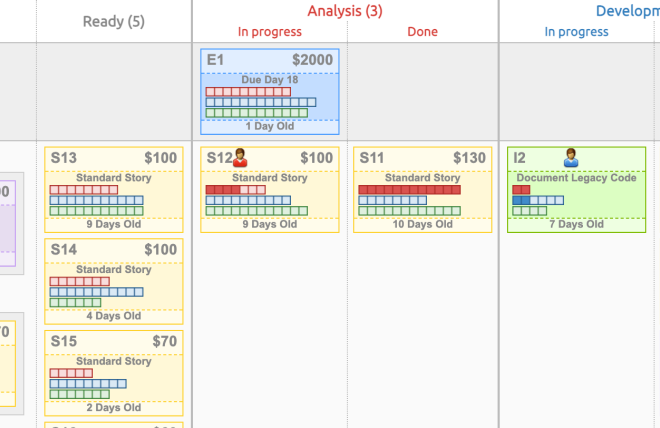

Flow Sensei helps teams and leaders build systems that work with people, not against them. And if this article struck a chord, you’ll love our Kanban trainings — practical, engaging, and rooted in the real challenges teams face every day.

YES. We Kanban..

Certified Kanban Trainings

Improve flow in your organization with Kanban.

Our trainings are defined by an engaging and supportive learning atmosphere – shaped by experienced trainers who combine strong facilitation skills with deep, real-world expertise.

Through their ongoing work with teams and organizations, they bring broad insights and concrete examples that make the content relatable and memorable.